An experienced teacher assesses her students constantly. While some may think of assessment in its more formal terms, like formative vs. summative, teachers know that assessment is an ongoing, instantaneous, and fluid process.

- When a student makes a strange face as I read the instructions, I assess the situation and realize I need to clarify.

- When three students ask me if they can ignore the word count, I assess the situation and realize that we need a mini-lesson on editing for brevity.

- When an English Language Learner student moves from zero speaking in class to speaking in Spanish to discuss the reading with classmates, I assess the situation to realize that she is buying into the class and her identity as a student.

But the problem with all three of these situations is that they are teacher-centric. Of course, as the teacher, I need to be aware of what’s going on. But arguably more important is for students to develop the skill of self-assessment, so they can begin to monitor their own progress and make adjustments that help them to maximize their learning.

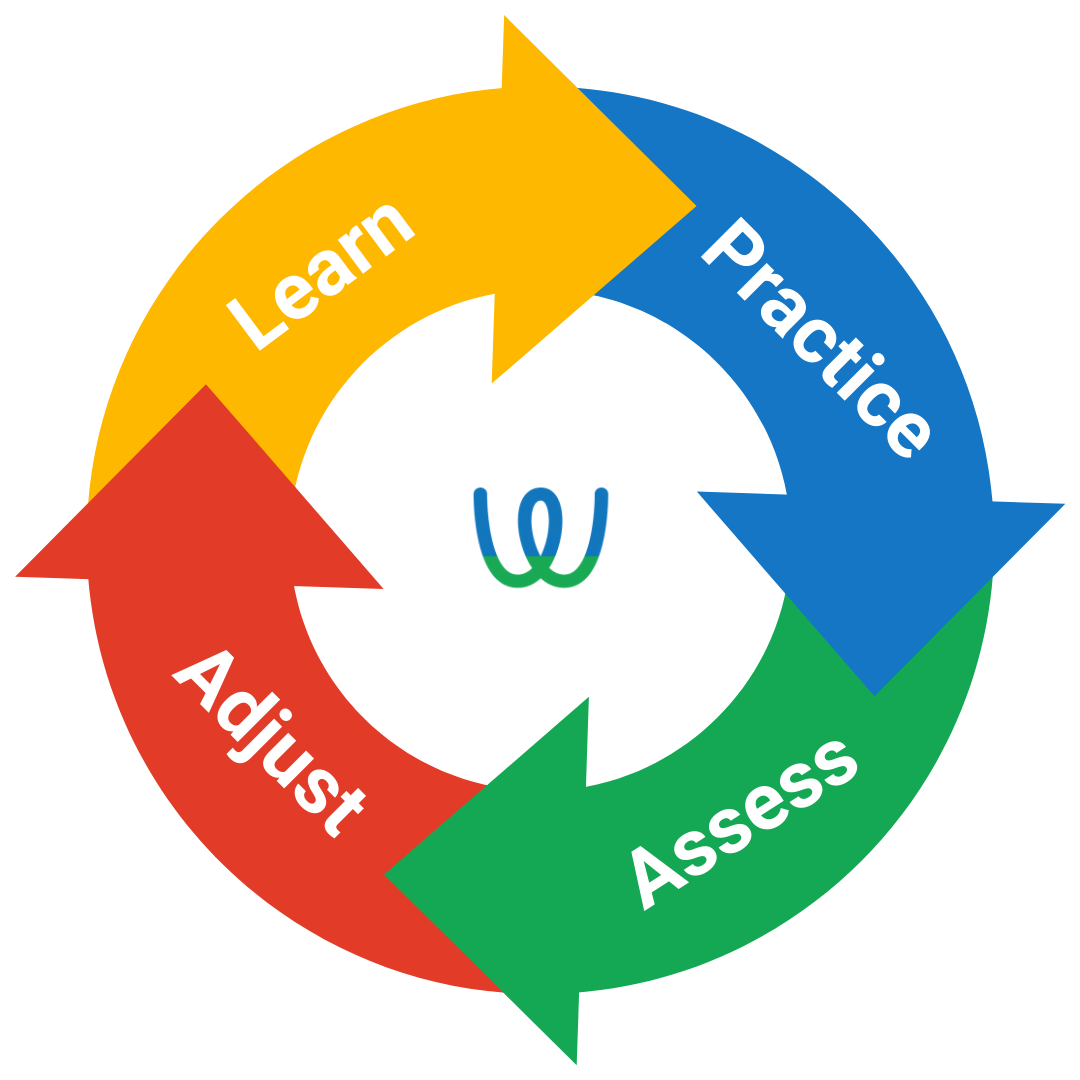

A big shift in my instruction came when I realized that assessment is not an endpoint; it’s a step within a recursive cycle of learning.

This is how the author visualizes assessment as part of the learning process.

After having this realization, I began to place a new focus on feedback. This came with its own set of challenges and questions, including:

- How to best give feedback: Comments? Conferences? Rubrics?

- How much feedback to give?

- How to find the time to make feedback happen?

As I worked through these issues, I realized the ultimate goal of feedback is to have students make meaningful improvements to their work and meet expectations or standards.

So what if students were equipped to evaluate their own work, give themselves feedback, and move through the learning cycle more independently? This would lead to a more efficient learning process, and no more bottleneck waiting for the teacher to assess everyone.

Two simple steps to help students self-assess

So I began using self-assessment in very simple forms, starting with a self-assessment based on a daily goal. Inspired by Jane Pollock’s book Feedback, I started to write an objective or “goal” on the board every day, asking students to begin class by copying the goal. Then, students gave themselves a numerical ranking, 1-5, based on how well they think they could meet that goal before the lesson even began. Class ended with students re-assessing themselves in order to notice any improvement they had during the instruction and practice that day.

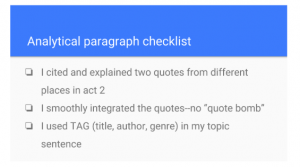

Moving forward, I integrated checklists into the writing process. The checklist was very simple, and I would simply list the expectations for the assignment in a statement form like this:

There are a few great things about using checklists like these as part of the writing process. First, these are very simple for teachers to make. You have already laid out the expectations for the assignment. Now, you can put these expectations in checklist form, and they become an interactive self-assessment tool for students. Second, these checklists can drive revisions and editing. When a student cannot yet check a box on the list, the student knows that he must return to his writing and revise it in order to meet the missing expectations. Lastly, checklists can encourage students to think creatively about how to move beyond the expectations for the assignment. To do this, ask students: what can you do, that is not listed on the checklist, to move beyond the expectations for the assignment?

How to make self-assessment part of the writing process

One of my beliefs as a writing teacher is that to be good writers, students need good taste. This means that students must see many examples of good writing, and they must be able to notice and discuss the traits of good writing. This happens before a student becomes a good writer. Self-assessment is part of this process.

When students are writing a piece that is based on personal ideas (an argument paper, a personal essay, or a narrative) as opposed to an analytical piece, I have them do an activity called Read Around Groups (RAGs). This is an activity that I learned from Kelly Gallagher’s book Teaching Adolescent Writers. The activity asks students to read anonymous sets of each other’s writing, and then cast votes about which paper in the set is strongest. Students repeat this process until they’ve read all the papers in the class. Remember, the reading is anonymous, so student names do not appear on the papers. Only code names are used.

After the votes are cast and one or two winners are chosen, the self-assessment begins. The class reads and discusses the winning papers. What made them great? What did the writers do well? And most importantly, what can we learn from these writers and apply to our own writing? Students write a short reflection describing the lessons they learned from the activity and naming a small number of revisions “moves” they can do to improve their paper.

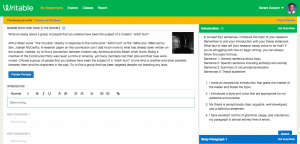

Starting last winter, I began to integrate Writable into my writing instruction. Why? It allows me to easily design self-assessment activities and build them directly into writing tasks. For example, my sophomore students researched and wrote about “modern-day witch hunts” during our study of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible. In this expository piece, I wanted students to be mindful of particular structural and stylistic elements of their writing, such as crafting an engaging introduction. Writable displays these expectations conveniently using “I” statements that students can easily use to reflect and self-assess while writing. Further, these same statements serve as criteria for peer evaluation after the draft is finished.

“Why are we doing this?”

All teachers hear this question, and it’s important for us to have reasonable answers. When it comes to self-assessment, students will not only improve their writing, but they will develop the valuable skill of self-awareness. In life, do we want students to have to wait for others to point out the errors of their ways, or would it be better if they could notice a false start and course correct on their own?

Comments are closed.